Soon the phrase “car talk” will mean a lot more than simply those occasions when petrolheads get together to chew the fat about horsepower, torque and turbochargers.

That's because cars are getting chatty. For all kinds of reasons, the vehicle you drive will soon be busy sharing information with other road users – as well as with traffic lights, road signs and assorted street furniture.

Why? It's part of the “long march” towards truly autonomous vehicles, says Nick Cook, chief innovations officer at technical consultants Intercede, which is advising many of the connected car trials currently underway in the UK and Europe.

These trials are paving the way towards an era when all cars are driverless, he says, by refining the information systems autonomous vehicles will need in order to operate. By gradually introducing connected cars to roads now, it will be possible to realise some of the benefits that will then increase when the majority of cars are able to drive themselves.

Cook looks forward to an era when cars can talk to the other vehicles around them as well as the signals that control the flow of traffic through urban areas or along a motorway.

“It becomes not just about the vehicle in front of you, but the vehicle in front of the lorry in front of you," he says.

“Traffic will be less stop and start, which will have a big impact on fuel savings, reduce the number of accidents and cut air pollution.”

Green lights

The trials are piloting different ways for trucks, cars and traffic lights to share data. Some put sensors on certain classes of vehicles, such as buses, to trigger traffic signals as they approach, helping them keep to their timetables. Others do the same for ambulances, constructing “green lanes” they can speed through to ensure they get the injured and sick to hospital as quickly as possible.

Smaller trials are looking at the effects of sharing information about speed among a few cars travelling close to each other, but independently, on faster roads such as motorways. Leading vehicles in these groups warn about what they see ahead, such as slow-moving traffic, and alert others if they will be braking sharply. Armed with that information, following vehicles can then compensate to avoid rear-end collisions or the kind of jerky driving that can cause phantom traffic jams.

While the end point of total autonomy is obvious, getting there will require a lot of intermediate steps, says Cook.

One problem that needs to be overcome is the “snooty” nature of existing cars. Most are great at gathering data about what they are doing, but few – so far – are sharing it. “Current in-vehicle architectures are not particularly designed to be connected,” says Cook. “That's because we've designed vehicles with little or no connectivity because it wasn't thought they would need it.”

Cars are now being built with their own unique net address or with a travelling Wi-Fi hotspot, but they are relatively few in number and tend to be expensive.

It's likely that early versions of inter-car communication will be via an add-on to existing vehicles, perhaps mediated by a smartphone. The information will be given to the human driver to act upon instead of letting the car decide.

Crashed traffic

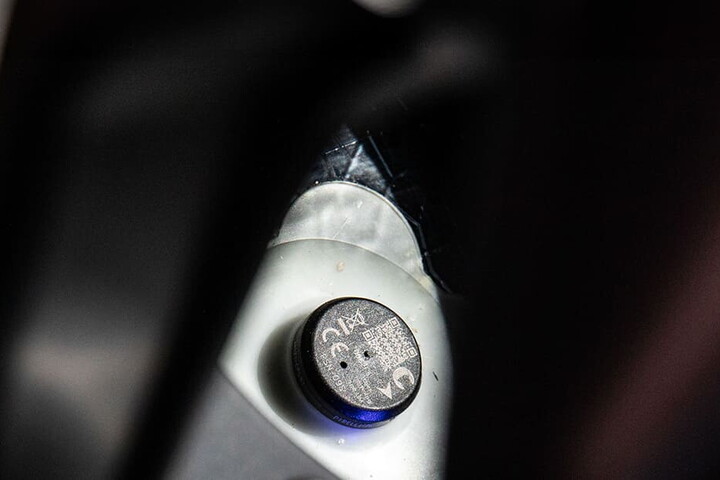

The trials are also working out which technologies are going to be most useful, says Cook. One issue that needs to be overcome is the speed at which data is shared. Some of the wireless data protocols suggested for connected cars are adapted from fourth and fifth-generation mobile phone technologies. That's more than fast enough for people, but for machines – which think much faster and need to react far more rapidly – it might not be quick enough. A rival standard, called Dedicated Short-Range Communications, is being developed that is tuned specifically for car-to-car data sharing.

And, of course, there's another major issue: security.

Cars are already data loggers, says security researcher Ken Munro, and the value of that data is apparent to insurers, who readily use it to see what happened in a crash or to assess your driving style and decide if you are a good or bad risk.

That data is only going to become more valuable – not least to the hackers, crackers and attackers who currently peddle viruses or launch online attacks. Problems could emerge through malice, mischief or mistake, says Munro, who recently found a bad security bug in one make of car.

“Consider if those communications between vehicles aren't properly secured,” he adds. “A hacker tells truck number two that he is truck number one and sends the message: ‘Follow me, turn right immediately to avoid an incident.'

“That could be the start of a really bad day.”